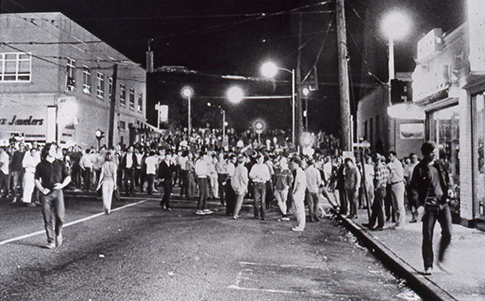

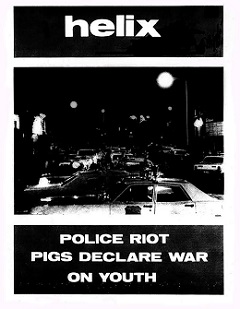

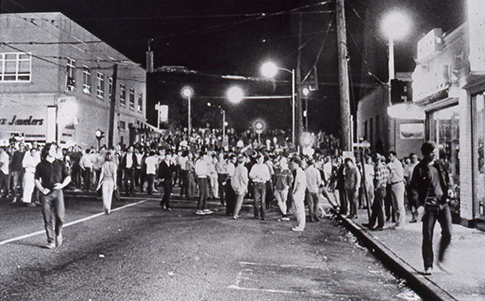

University Way Northeast and Northeast 43rd Street during the Ave riots

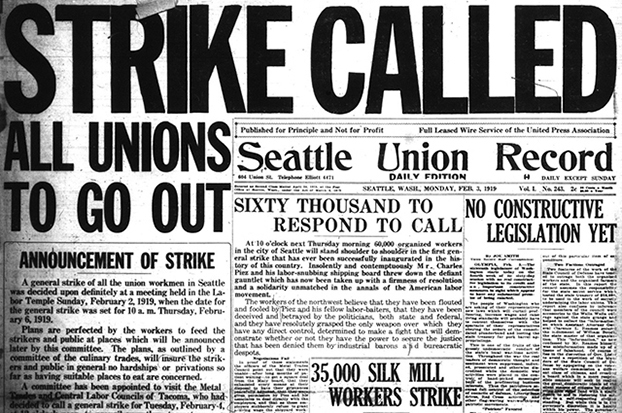

Stan Stapp

The summer of 1969 was a time of infamous turmoil in several major American cities, including Seattle. On the date in focus here, a series of riots began in the University District that would shake University Way Northeast — a.k.a. “The Ave” — over several days. During that week, street people on The Ave would battle with Seattle police, leading to multiple arrests and injuries and much vandalism and looting. While the origin of the riots remains contentious today, the aftermath would lead to significant changes in the character of the U District, both as a neighborhood and as a community.

The Ave riots were preceded by an incident across town in West Seattle the previous evening during a Sunday night rock concert at Alki Beach. Despite the concert being an officially permitted event, several Seattle Police Department (SPD) officers on the scene began harassing attendees. In response, someone — allegedly a member of a local motorcycle gang — dumped a container of gasoline into the back seat of an SPD patrol car and threw in a lighted match, setting the car ablaze. SPD, in counter-response, abruptly declared the concert over, donned riot gear, and began throwing canisters of tear gas into the crowd — not ordinary tear gas, but rather the CS variety, which sickens its victims. The thick toxic fumes drifted into the nearby neighborhood, thus transforming a peaceful rock concert into a major public disturbance.

The following day, in the U District, many regular denizens of The Ave shared news of the Alki fracas with disgust. SPD harassment of youth — especially countercultural youth — was a regular fact of life in that neighborhood at that time. (It was also then a regular fact of life citywide, which partially explained the heavy SPD presence at the Alki concert.) In fact, SPD presence in the U District had recently been doubled by Seattle’s acting mayor Floyd Miller as part of a crackdown on drug traffic in the neighborhood. Thus, as the evening of August 11 arrived, many on The Ave were ready for a confrontation with the cops.

And thus, the first riot on The Ave that week began at approximately 9 p.m. that night, when a random young man kicked over a trash can at the intersection of Northeast 42nd Street and The Ave. According to witnesses, SPD officers standing nearby quickly grabbed and handcuffed the vandal. His girlfriend then objected, screaming at the officers and pleading for bystanders to intervene. When the cops grabbed her next, one brave bystander punched one of the cops, Officer Mike Bolger, in the jaw, and the scuffle quickly escalated into a riot. Spectators began throwing everything they could get their hands on. Bricks struck two other officers, Marvin Queen and Thomas Grabicki, and a stray object shattered the window of the Coffee Corral, a popular hippie hangout on the southeastern corner of that intersection.

By 9:30 p.m., the crowd of rioters had grown to roughly 150. Witnesses later noted that many in the crowd had also been present at the Alki fracas. More police soon arrived, along with a TV news crew, but by 10:15 p.m. the rioters had drifted away and the police withdrew. All in all that night, seven rioters were arrested and three SPD officers were injured.

The next day, August 12, the U District was buzzing with news of the previous night’s incident. While The Ave was quiet that night, and SPD then kept a low profile, the following night would be a different story entirely.

While the riot on August 11 may have been politically motivated — some attributed it to the antiwar activists who were a regular part of the Ave scene at the time — the rest of the week’s rioting was evidently the initiative of restless teenagers from across the city coming to the U District strictly for kicks, lured by news of Monday’s incident. The most intense and destructive of the riots would occur on the nights of August 13 and 14 — and most regular U District denizens who witnessed the riots later claimed they did not recognize most of the participants on those nights.

The evening of August 13 began with a spontaneous community meeting of about fifty people at 7:30 p.m. on “Hippie Hill,” the stretch of lawn on the University of Washington campus near the intersection of 15th Avenue Northeast and Northeast 42nd Street, then a popular gathering place among Seattle’s countercultural community. The meeting was called to discuss the recent disorder in the U District. Much anger was vented there concerning SPD harassment, but the apparent consensus was that people should avoid further cop confrontations.

Among the topics of discussion was a pair of flyers that had been circulating in the neighborhood since the morning of August 12. One urged calm in the name of “the New American Community,” while the other was unsigned and much more militant, bearing a sketch of a pistol with the caption “We’re looking for people who like to draw,” an apparent parody of the matchbook ads for art school so common at the time — and an obvious attempt at violent provocation.

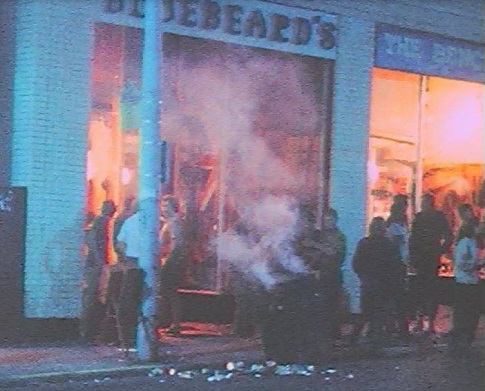

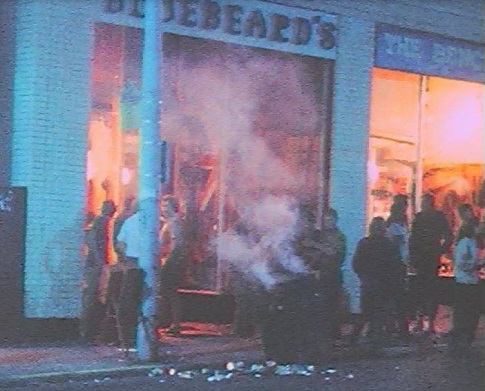

After the meeting on Hippie Hill adjourned around 8:30 p.m., several attendees headed towards The Ave and immediately noticed two strange things: there were no police visible anywhere; and The Ave was filled with hundreds of teenagers, both white and Black, whom no one at the meeting had ever seen in the U District before. All was calm until around 9:30 p.m., when a group of the unfamiliar teenagers began looting Bluebeard’s, a hippie boutique on the western side of the 4200 block of The Ave. Several locals tried to intervene, proclaiming that Bluebeard’s wasn’t the enemy — but to no avail.

Meanwhile, no police appeared, despite the returning chaos. Someone dragged a trash can onto The Ave and lit it on fire — still, no police came.

Outside Bluebeard’s boutique, August 13, 1969

photographer unknown

The cops finally appeared at precisely 10 p.m., when a banshee wail erupted from the roof of the Adams Forkner Funeral Home on the eastern side of the 4100 block of The Ave, where SPD had installed a “howler,” a high-frequency noise generator designed to disorient crowds. Moments later, a loudspeaker announced, “You are ordered to disperse. If you do not disperse, you will be removed by force.”

Soon afterwards, scores of Tactical Squad officers in full riot gear charged onto The Ave from nearby alleys, and CS gas grenades began exploding. The rioters, undeterred, began pelting the police once again. As the chaos quickly escalated, trash cans were ignited to bait the police, parking meters were smashed, and stores were looted. Meanwhile, on 15th Avenue Northeast, a mobile crane was set on fire, and when firemen arrived they had to withdraw under a hail of stones.

Around 11 p.m., the Neptune Theatre’s evening showing of Franco Zeffirelli’s hit film Romeo and Juliet ended, and hundreds of moviegoers — many themselves young people, the film’s target audience — exited into the middle of the chaos. They were promptly attacked and gassed by police as they attempted to return to their cars. Amazingly, SPD never blocked off traffic along The Ave, and several motorists at the intersection of The Ave and Northeast 45th Street found themselves trapped among clouds of tear gas and agitated hordes of teens and police.

The chaos that night continued until 3 a.m., and the night of August 13 ended with 21 rioters in jail and three SPD officers in the emergency room.

The night of August 14 was almost an exact replica of the previous night. As dusk fell, roughly two thousand young people from outside the U District gathered on The Ave, obviously anticipating further violence. The events of the previous night began to replay promptly at 10 p.m., when a group of teenagers broke into a TV repair shop on the northwestern corner of The Ave and Northeast 43rd Street, and also began looting other stores nearby.

Squads of cops quickly appeared at that intersection, coming from both north and south and surrounding a crowd of about two hundred, while a truck-mounted howler sonically swept the street. The cops ordered the encircled mass to disperse — but when the officers moved in, there was nowhere for the crowd to go. Finally, the police opened a narrow gap onto 43rd Street, and people ran out through a gauntlet of clubs and fists.

Another crowd gathered at Northeast 45th Street and 15th Avenue Northeast and trashed the brand-new plate-glass windows of the Pacific National Bank building before police chased them away. Eventually, the cops grew tired of the cat-and-mouse fracas and closed The Ave to automobile traffic, then gassed the street from 42nd to 45th with foggers and grenades. All in all that night, the police arrested 21 rioters and roughed up five local news reporters, including KOMO-TV’s Don McGaffin and Brian Johnson. Order was finally restored just before one o’clock in the morning.

On August 15, in the aftermath of the riots, SPD finally detoured traffic from The Ave while volunteers spread out to prevent any further unrest among teenagers. As the community discussed what to do next, everyone agreed that SPD could neither prevent nor contain any further violence in the neighborhood. The city was considering ordering a curfew and summoning the National Guard when a delegation of community leaders from the U District met with Acting Mayor Miller and Deputy Mayor Ed Devine. After that meeting, SPD agreed to step back and let the community try to handle the situation.

SPD closed The Ave to traffic at dusk and parked several hundred Tactical Squad officers out of sight nearby, while several volunteers wearing peace-symbol armbands spread out along The Ave. Whenever a significant number of teenagers gathered there, street monitors stepped in to prevent any attempts at looting or vandalism. The same tactic was repeated the following night with equal success. By Sunday, August 17, The Ave was back to normal and SPD finally withdrew.

The success of the U District community’s response to the Ave riots led to months of negotiations among street people, merchants, residents, clergy, students, police, and municipal officials, all aiming to reduce police harassment and to establish a community center. Not all of this coalition’s goals were realized, but the U District would become a much more closely-knit neighborhood as a result of the collective catharsis.

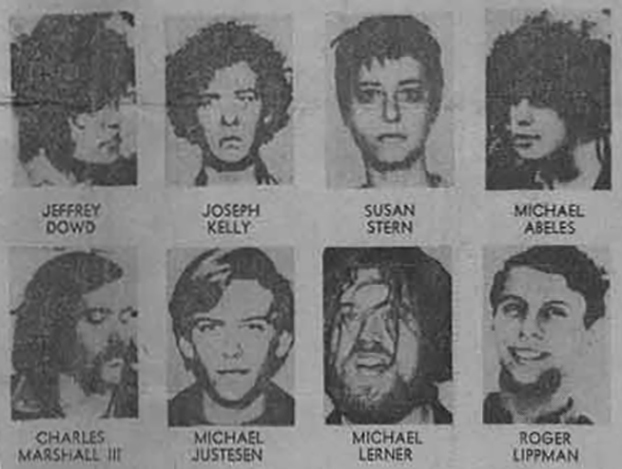

Among the other aftermaths of the Ave riots, several of the women who participated later came together and formed the core of the Seattle Weathermen — crucially including radical feminist and antiwar activist Susan Stern (1943-1976), who later became one of the legendary Seattle Seven. Stern would eventually present her own particular interpretation of the sociopolitical context of the Ave riots in her 1975 memoir With the Weathermen: The Personal Journal of a Revolutionary Woman.

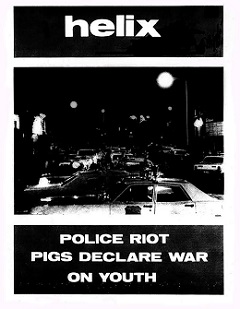

Helix, August 14, 1969

Who provoked the Ave riots? Some said it was political agitators; some said it was juvenile delinquents; some said it was the cops. For a few years prior, Seattle police had been constantly harassing countercultural youth, mostly at the behest of business owners in the U District and elsewhere in the city who loathed the hippies’ local presence. While SPD Chief Frank Ramon told The Seattle Times that the riots were simply “violence for the sake of violence,” members of the local countercultural press had a much different explanation. In a commentary on the riots published the following week in Helix — then Seattle’s reigning underground newspaper, founded in the U District — Helix editor Walt Crowley (1947-2007) explained the profoundly volatile situation which had likely set the stage for the riots:

“Since 1966 when the aberrant individuality of the Beatniks gave way [to] en-masse migration of middle-class youth from the suburbs, the University District has become the scene of ever-growing police harassment and internal conflict. Merchants and long-time residents, disturbed by the influx of unorthodox young people, loitering and drug traffic, have applied economic pressure against their long-haired tormentors and sought police cooperation. In the name of ‘cleaning up the District’ hippies have been discriminated against by retailers, restaurants, and realtors. They have been subjected to arbitrary law enforcement, harassment, and brutality and humiliation at the hands of the police. Thus over the past four years the tension has slowly grown and the antagonism between the various sectors sharing this same geographical area has deepened and entrenched.”

Despite the initial drama and trauma of the Ave riots, positive and permanent outcomes resulted from the event, including and especially the annual University District Street Fair, Seattle’s first modern street fair, which continues today. Organized by the University District Chamber of Commerce as one means among many of healing the neighborhood in the wake of the riots and other tumultuous events in the U District during the preceding year, the first University District Street Fair was held during the weekend of May 23 and 24, 1970.

–Jeff Stevens. Sources: Lou Corsaletti, “Tear Gas at Alki Beach Justified, Says Ramon,” The Seattle Times, August 11, 1969, p. 1; Roger Yockey, “Gas Bomb Flies Into Home, Explodes,” The Seattle Times, August 11, 1969, p. 4; John Hinterberger, “Beach Residents Still Smarting From Leftover Tear Gas,” The Seattle Times, August 11, 1969, p. 9; Paul Henderson, “Police Study Damage, Complaints After Alki Disturbance,” The Seattle Times, August 11, 1969, p. 9; “3 Officers Hurt in Melee,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, August 12, 1969, p. 1; “Ramon Claims Alki Tear Gas ‘Best Alternative’ in Fray,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, August 12, 1969, p. B; Lou Corsaletti, “U. District, Alki Disorders Planned, Says Chief Ramon,” The Seattle Times, August 12, 1969, p. 1; John Hinterberger, “Merchants Worried, Relieved After Fracas,” The Seattle Times, August 12, 1969, p. 15; Mike Wyne, “3 Officers Hurt In Youth Melee,” The Seattle Times, August 12, 1969, p. 41; “‘Fed Up,’ Says U Area Merchant,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, August 13, 1969, p. 1; “After Tear Gas, Child Fears Police” (letter to the editor), The Seattle Times, August 13, 1969, p. 11; Walt Crowley, “Power vs. People,” Helix, August 14, 1969, p. 2; “Police Battle Rock-Hurling, Looting Gangs in U District,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, August 14, 1969, p. 1; “U District Has Look of War,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, August 14, 1969, p. 12; John Hinterberger, “Police Showed Restraint Before Violence Erupted in U. District,” The Seattle Times, August 14, 1969, p. 1; “Chief Ramon Calls Violence ‘Planned Attack on Police’,” The Seattle Times, August 14, 1969, p. 1; “University Area Merchants Urge ‘Reasonable Force’,” The Seattle Times, August 14, 1969, p. 3; Shelby Gilje, “‘Unbelievable’: U. District Movie Treat Turns To Terror for Mother, 2 Girls,” The Seattle Times, August 14, 1969, p. 7; Mike Wyne, “21 Arrested, Three Injured as Youths, Police Battle,” The Seattle Times, August 14, 1969, p. 8; John Hinterberger, “It Began on 2 Notes: Retaliation . . . Restraint,” The Seattle Times, August 14, 1969, p. 8; “Police Riot-Control Tactics” (editorial), The Seattle Times, August 14, 1969, p. 10; “Looting, Smashing Youths Run Wild On U Way Again,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, August 15, 1969, p. 1; “U District Merchants Support Police Action,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, August 15, 1969, p. B; James C. Lewis, “(Teary) Eyewitness at Riot,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, August 15, 1969, p. B; “Mayor Studies Need For U. District Curfew,” The Seattle Times, August 15, 1969, p. 1; Mike Wyne, “23 Persons Arrested,” The Seattle Times, August 15, 1969, p. 2; “Injured,” The Seattle Times, August 15, 1969, p. 2; Susan Schwartz, “Some Watched, Others Acted,” The Seattle Times, August 15, 1969, p. 2; “Police-Baiting That Backfired” (editorial), The Seattle Times, August 15, 1969, p. 10; “Clothing Store Loot Loss $2,012,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, August 16, 1969, p. B; “Lull Settles on U District,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, August 16, 1969, p. B; Mike Wyne, “Role-Switching Works to Cool U. District,” The Seattle Times, August 16, 1969, p. 8; “Bluebeard’s Loss Exceeds $2,000,” The Seattle Times, August 16, 1969, p. 8; Julie Emery, “U. District ‘Cool-It’ Movement Praised,” The Seattle Times, August 16, 1969, p. 8; “15 Plead Innocent To U. District Disturbance,” The Seattle Times, August 16, 1969, p. 8; “Police Force In U District To Be Cut,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, August 17, 1969, p. 6; Don Hannula, “U. District Acts to Defuse Tensions,” The Seattle Times, August 17, 1969, p. 1; “Candidate Criticizes Unrest Handling,” The Seattle Times, August 17, 1969, p. 25; Michael J. Parks and Paul Andrews, “The University District: Both Sides Share Blame, Witnesses to Disorders Agree,” The Seattle Times, August 17, 1969, p. 49; “Helix Riot Report,” Helix, August 21, 1969, p. 8; Susan Stern, With the Weathermen: The Personal Journal of a Revolutionary Woman (Doubleday & Company, 1975; Rutgers University Press, 2007); Walt Crowley, Rites of Passage: A Memoir of the Sixties in Seattle (University of Washington Press, 1995).